Our Company History in Fast Motion

1849 – 1913

1849

Establishment of the company

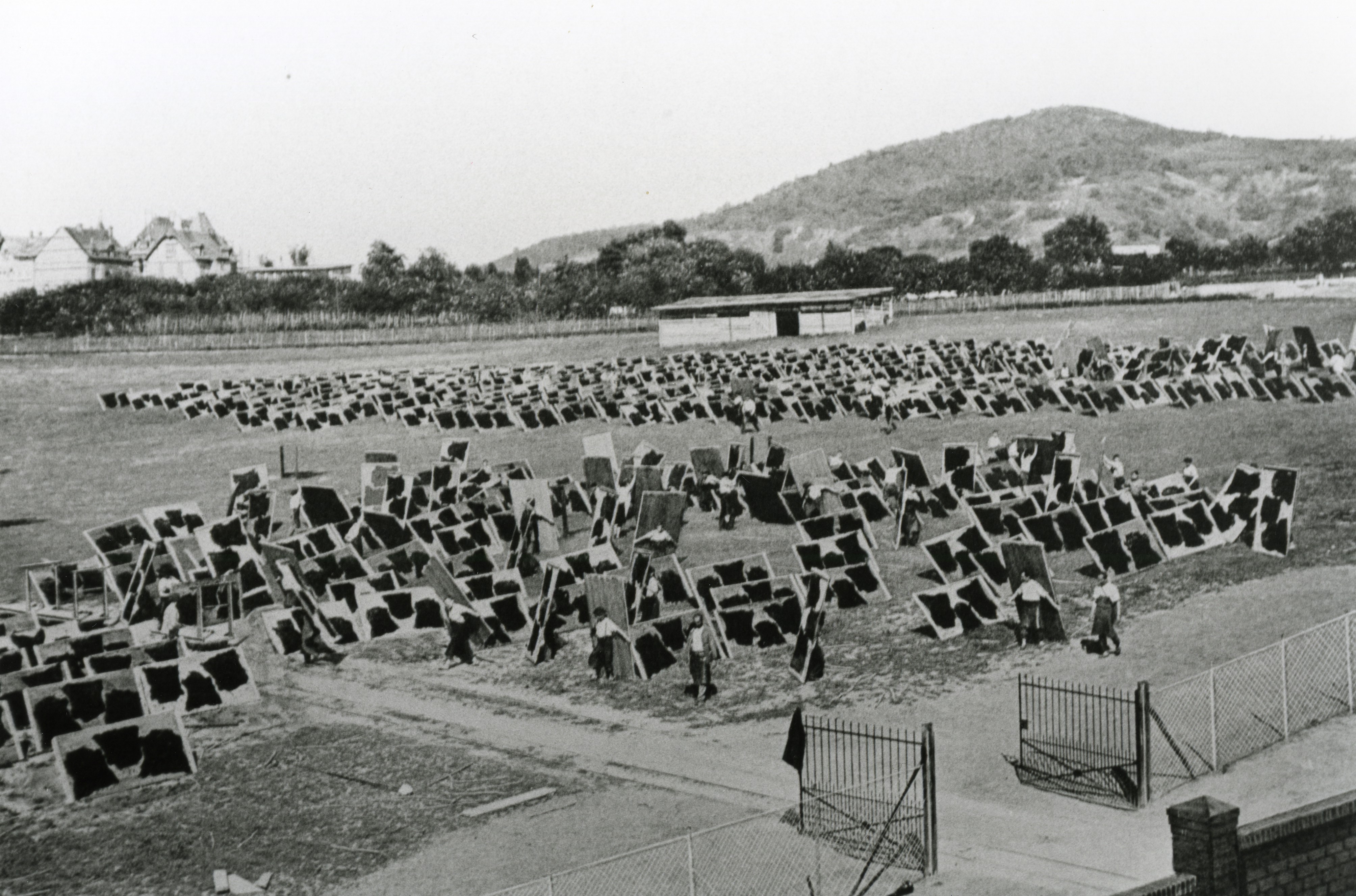

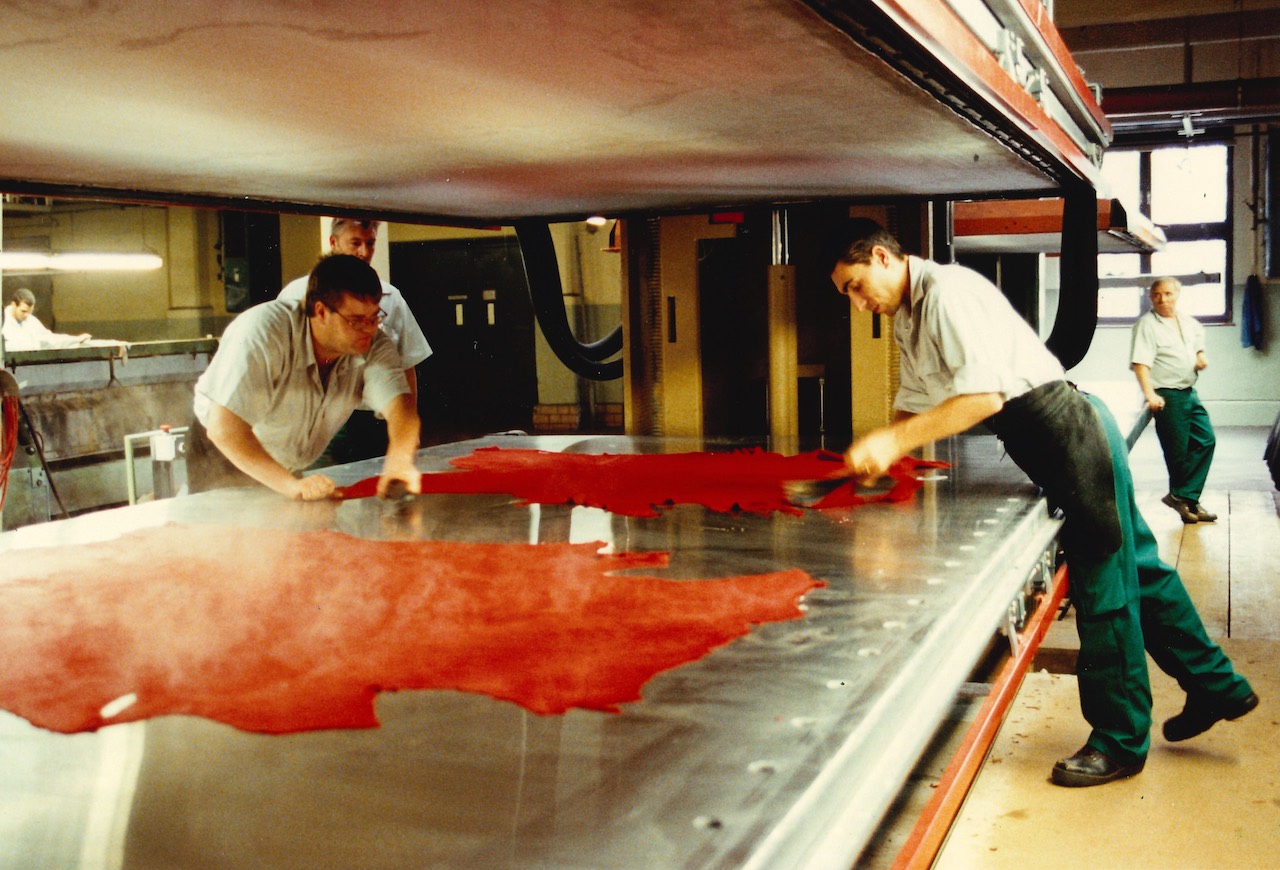

Amidst the turmoil of the Baden Revolution, the tannery Heintze & Freudenberg is established by partners Carl Johann Freudenberg (1819-1898) and Heinrich Christian Heintze (1800-1862) on February 9, 1849. The company employs 50 workers and produces fine calf leather.

A lively international trade (including exports to the USA, Great Britain, France, and Turkey) flourishes from the beginning.

1850

First innovation: patent leather

One year after the company is founded, Freudenberg develops its first innovation: the company begins to thrive after introducing patent leather in 1850 and develops into the largest tannery in Germany in the following years.

1874

Carl Johann Freudenberg becomes sole owner

Carl Johann Freudenberg becomes sole proprietor. The company is renamed Carl Freudenberg.

1887

Second generation on the Management Board

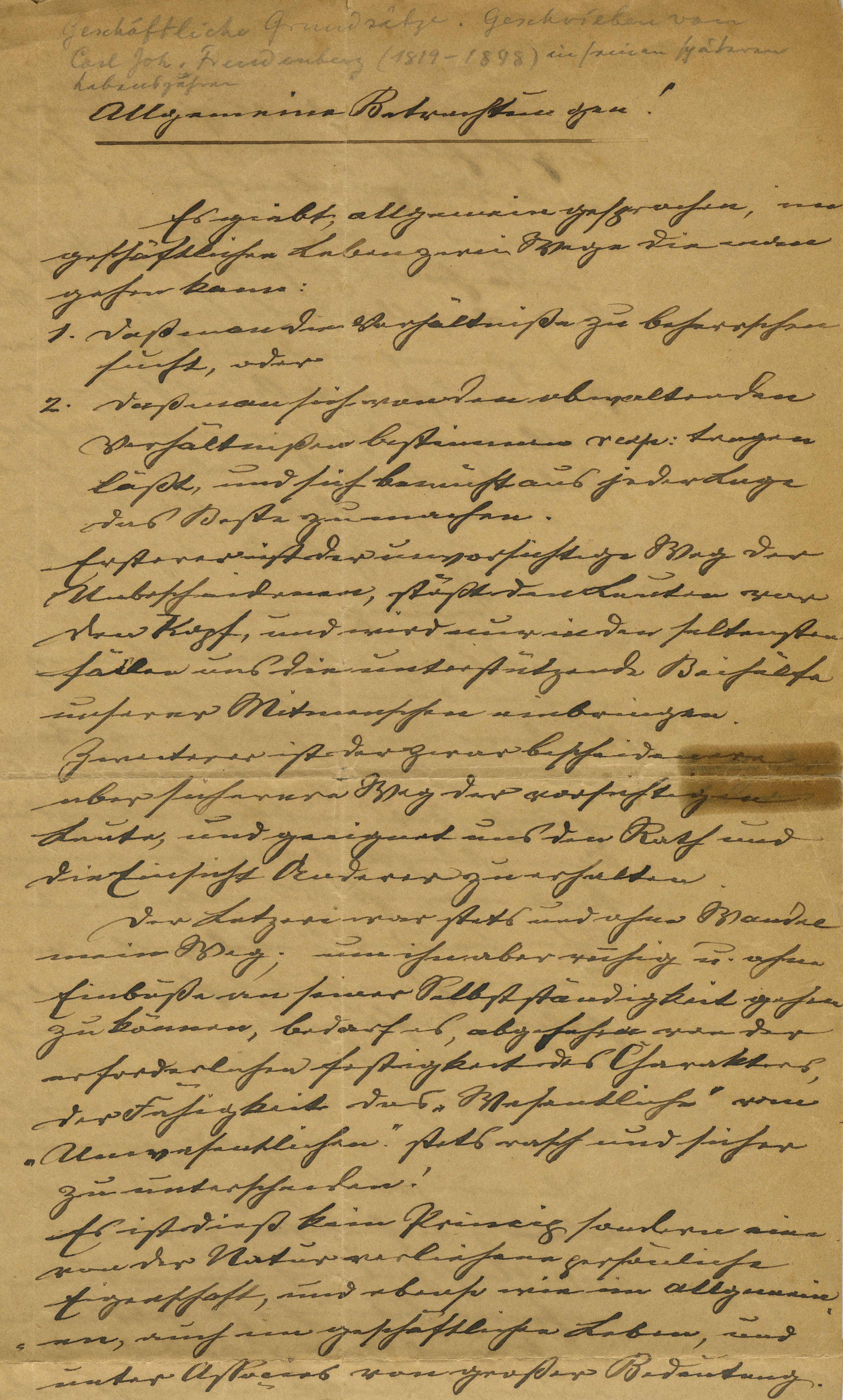

In 1887 Carl Johann Freudenberg introduces the next generation. His sons, Friedrich Carl (1848–1942) and Hermann Ernst Freudenberg (1856–1923) become partners. At this time, Carl Johann Freudenberg writes down his business principles. Modesty, honesty, a solid financial foundation and the ability to adapt to the respective changes were his most important principles for successful entrepreneurship. Today, these Guiding Principles form the basis of Freudenberg’s Business Principles.

1904

Chrome tanning developed

Between 1900 and 1904, using his own experiments, Hermann Ernst Freudenberg develops the chrome tanning process, which is already being practiced in the US. Freudenberg is one of the first leather producers in Europe to produce high-quality, chrome-tanned calf leather. With the introduction of chrome tanning, Freudenberg becomes the largest leather manufacturer in Europe.

1914 – 1932

1914 – 1918

Freudenberg during World War I

At the outbreak of the First World War, the company employs more than 2,500 people. Due to the sharp, war-related decline in orders and conscription for military service, the number of employees drops significantly. The women take on some of the conscripted men’s work until they return. After the war, global trade relations are re-established and expanded, even reaching South America, Asia, and Australia.

1929

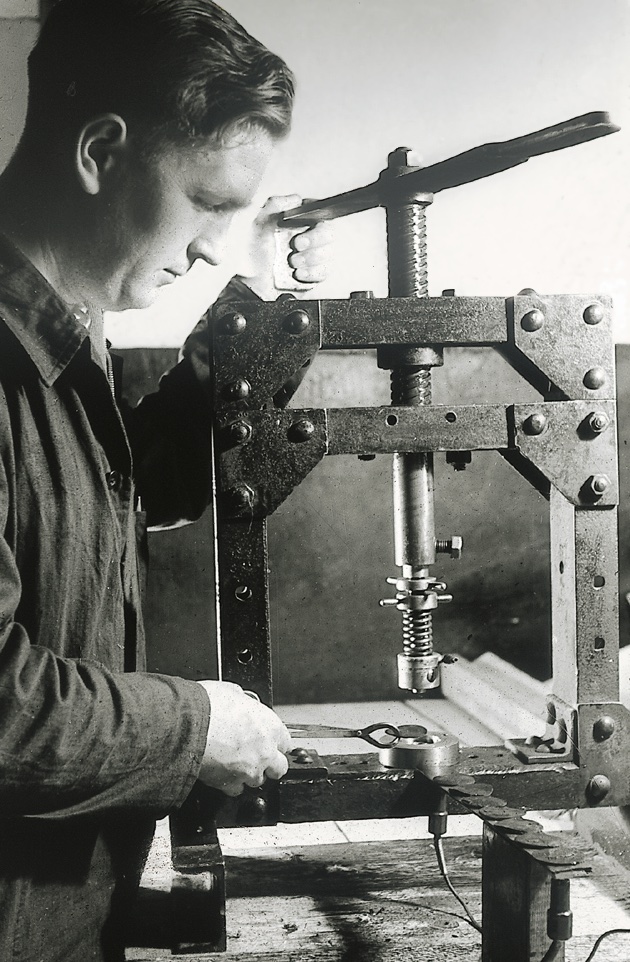

First seals produced

The global economic crisis affects the entire leather industry in Germany, seriously threatening its viability. To secure the jobs of its more than 3,500 employees at the time, the management develops its own short-time working model.

The difficult economic situation leads the management team to introduce diversification to the company with entirely new products. The first step is the introduction of leather sleeve seals for the growing auto industry in 1929.

1932

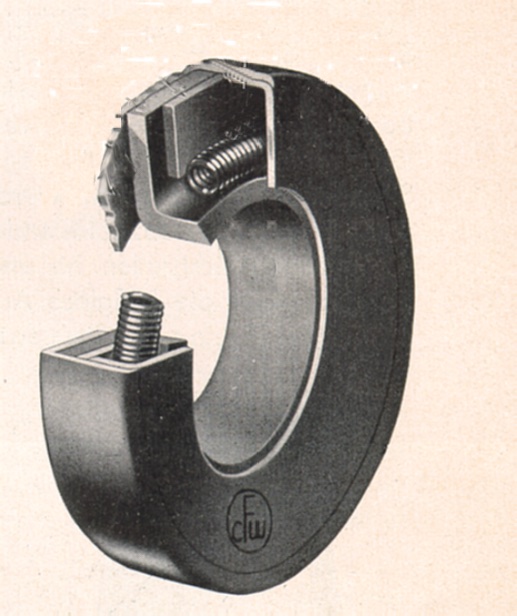

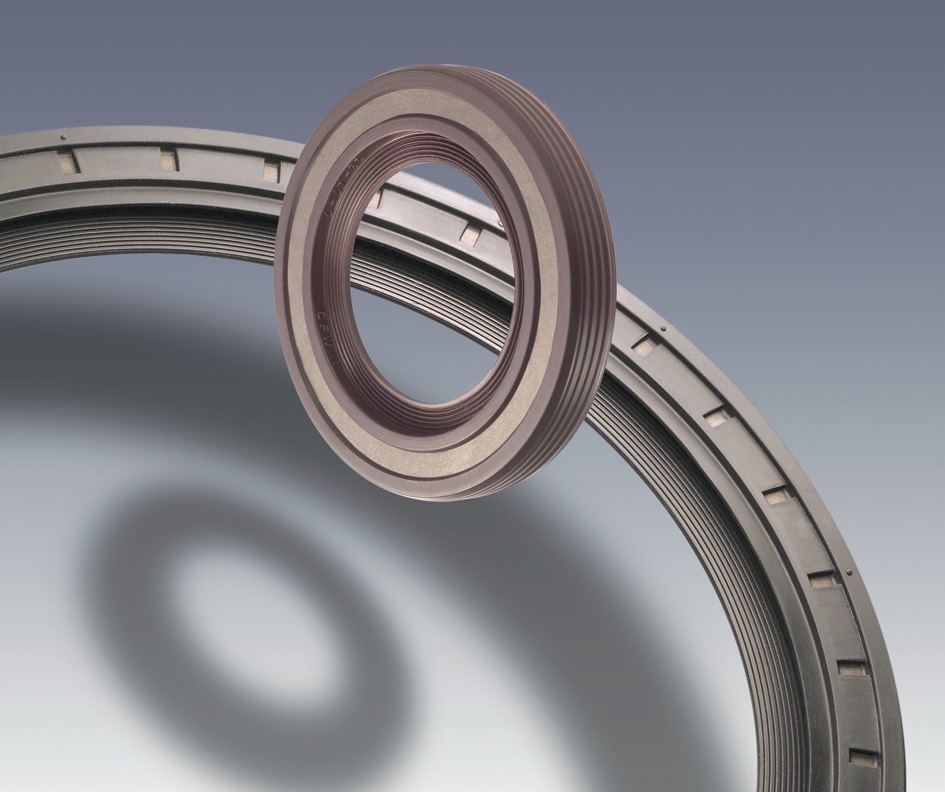

Simmerring® developed

With the revolutionary Simmerring®, a new era at Freudenberg begins: sealing technology. Its name is taken from the Freudenberg developer Walther Simmer. The Simmerring®, a radial shaft sealing ring for rotating shafts, replaces the felt seals previously used.

1933 – 1945

1933

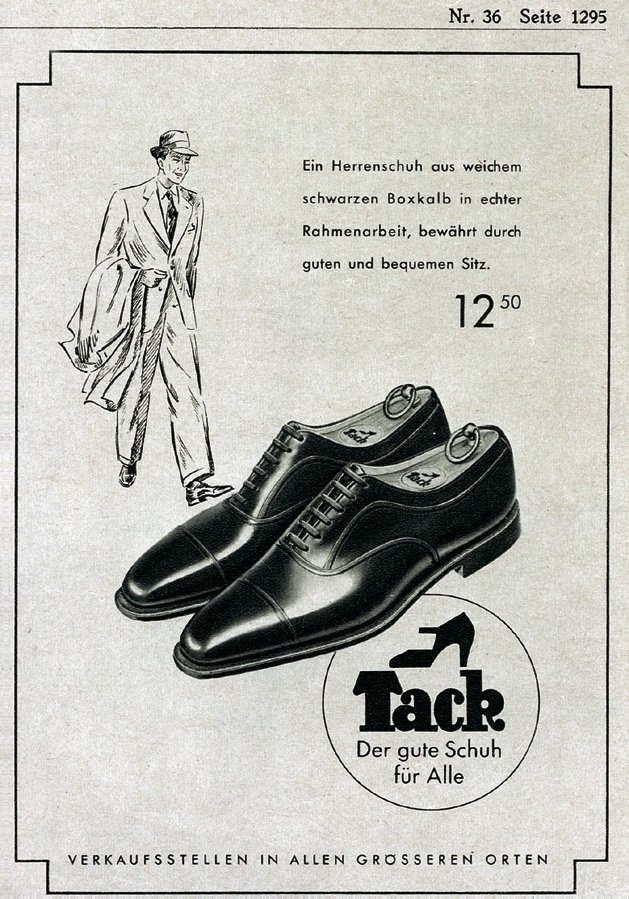

Entry into shoe business / Start of Nazi dictatorship

Freudenberg takes over the shoe production and commercial chain of the Jewish-owned company Conrad Tack in Burg, near Magdeburg. Between 1933 and 1936, Freudenberg assumes control of the Gustav Hoffmann children’s shoe factory in Kleve, Germany, and its elefanten® brand. Freudenberg further expands its shoe and leather activities between 1937 and 1938 via different “Aryanizations” of Jewish companies. This also includes the equine leather business of the Jewish company Sigmund Hirsch in Weinheim, with which Freudenberg has good relations.

At the time, the members of the company’s management board are civic-economic proponents of the Weimar Republic. Their outspoken criticisms of Hitler, made especially by Richard and Walter Freudenberg in 1932 and 1933, show them to have been committed democrats. However, in the years after the Nazis seize power they increasingly come to terms with the totalitarian system, to the extent that the company continues to benefit from Nazi economic policy up to the final collapse of the regime.

1934

Main laboratory established

The National Socialists’ self-sufficiency efforts make it increasingly difficult to import enough rawhide for leather production. In 1934, there is therefore a leather shortage in Germany. Freudenberg responds by establishing the main laboratory. The first projects involve the utilization of skin and leather waste from the tannery and the search for leather substitutes. Research soon focuses on elastomers for the modification and further development of Buna synthetic rubber. The result is Perbunan, a base material for new Freudenberg products.

1936

Simmerring® with rubber sealing lip developed

Freudenberg replaces leather with rubber as a sealing material. In 1936, a sealing ring made of Perbunan/NBR is developed: It has a high temperature and swelling resistance when exposed to engine lubricating oil. The NBR Simmerring® is a quantum leap for sealing technology.

1938

Nonwoven production begins

As a further response to the leather shortage in Germany from 1934 onwards, Freudenberg develops the synthetic latex artificial leather Viledon as a substitute material for bags and suitcases. The backing material for the artificial leather is a nonwoven that Freudenberg began developing in 1936.

The synthetic rubber NBR is also used for nora® shoe soles, which are mass produced from 1938.

1939 – 1945

Freudenberg during World War II

The diversification begun before the war makes it easier to compensate for the difficult raw materials situation than in World War I, as the company is no longer exclusively in the leather business.

During the war, Freudenberg is also a supplier to the armaments industry. The main products involved are gaskets for various military applications, in particular for vehicles, as well as shoes and artificial leather products for the Wehrmacht.

Due to scarcity during the war, the Nazi authorities look for ways to improve the properties of shoe components. In May 1940, the Reich Office for Economic Development therefore establishes a shoe-testing track in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. This continues to be operated by the SS as a punishment detail until the spring of 1945. Materials from at least 79 companies are tested there, one of which is Freudenberg.

Because of wartime labor shortages, Freudenberg employs forced laborers between 1940 and 1945.

1946 – 1997

1948

Start of production of Vileda cloths

At the end of the war, nonwoven backing material is refined. In 1948, production begins for nonwoven-interlinings for the textile industry and Vileda cloths made from nonwovens.

At this time, the company employs more than 5,000 employees.

1950

First foreign production company / Development of rubber floor coverings

The company expands at home and abroad. The first foreign production company is built in the USA in 1950. Interlining for the clothing industry is manufactured in Lowell, Massachusetts. This is followed by subsidiaries and investment in Great Britain, France, the rest of Europe and finally in the Far East.

The company opens another product area: In 1950, the nora® rubber floor covering brand is introduced as a development of nora® shoe soles. In 2007, Freudenberg separates from its floor covering business.

1957

Entry into vibration control technology and filtration technology

Freudenberg becomes involved in vibration control technology, which complements its expertise from sealing technology. The company produces shock absorbers, antivibration mountings and ultra bushings. In the same year, the product area of technical nonwovens is established with its first filters.

1960

First partnerships in Japan

This year marks the beginning of two formative partnerships in Japan. Freudenberg forms a close partnership in sealing technology with the Nippon Oil Seal Industry Company (NOK) in Tokyo. In the nonwovens sector, Freudenberg establishes a Joint Venture with Japanese partners: the Japan Vilene Company in Tokyo.

At this point, Freudenberg has more than 11,000 employees.

1966

Klüber Lubrication acquired

Freudenberg acquires Klüber Lubrication in Munich, Germany, thus opening a completely new business area with chemical products.

1970

New production technology for spunbonded nonwovens

The new production technology for spunbonded nonwovens, developed by the company, allows the production of nonwovens for new application areas, such as wound dressings in medical technology and nonwovens in agriculture.

1989

First car cabin filters / FNGP established

The first micronAir® brand car cabin air filters are introduced in 1989. Today, Freudenberg is the world market leader in car cabin air filters.

The American sealing activities by Freudenberg and its Japanese partner NOK are introduced in a joint venture: the Freudenberg-NOK General Partnership (FNGP).

1997

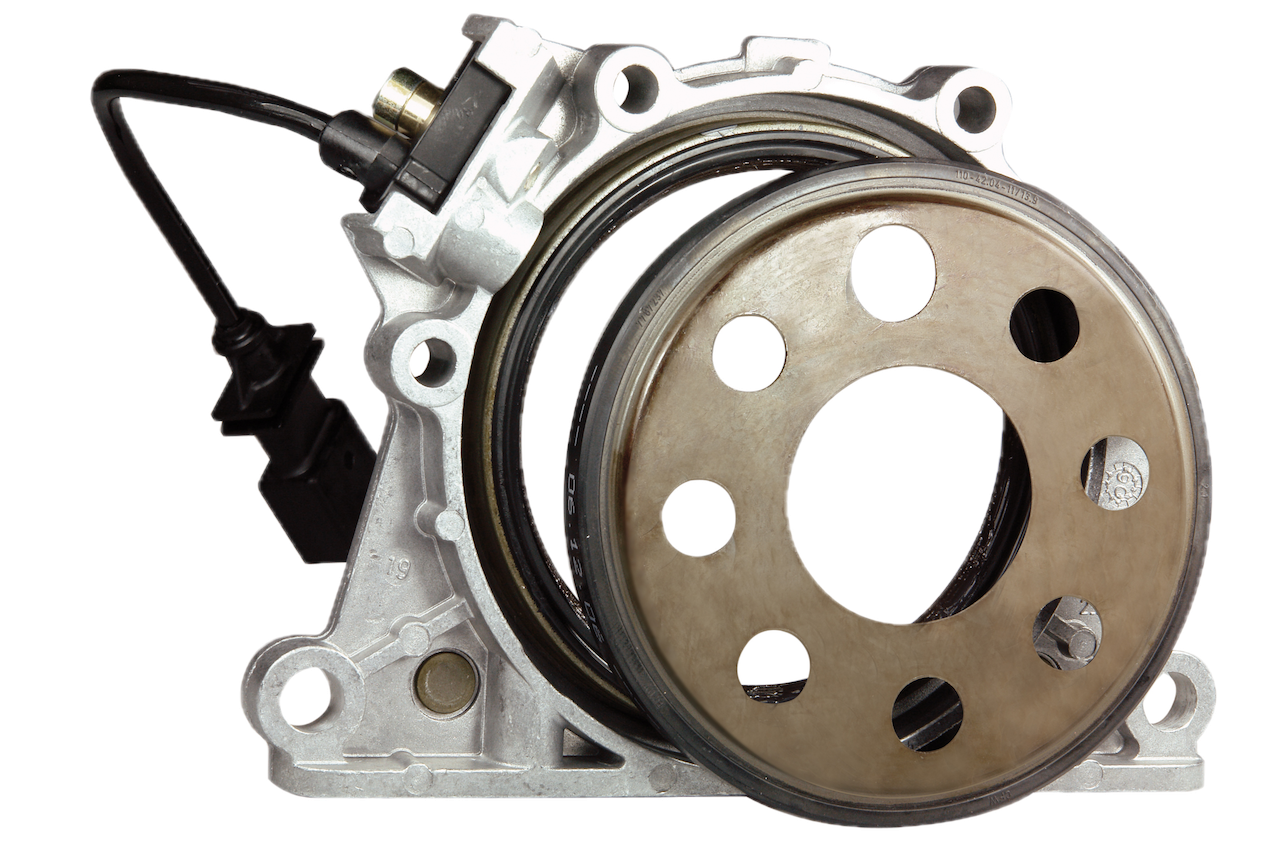

First mechatronic sealing components / Politex established

The Simmerring® takes on additional functions. Encoder technology is developed and the seal becomes a product that performs tasks beyond sealing. With integrated sensor technology, the encoder can measure the engine revolutions, making it possible to control anti-lock braking systems (ABS) and engine management systems.

In the same year, Freudenberg Politex Nonwovens SpA is established in Novedrate, Italy to produce polyester nonwovens made from recycled PET bottles. In 2004, Freudenberg assumes 100% control of the joint venture with Italian partners.

1998 - 2007

2001

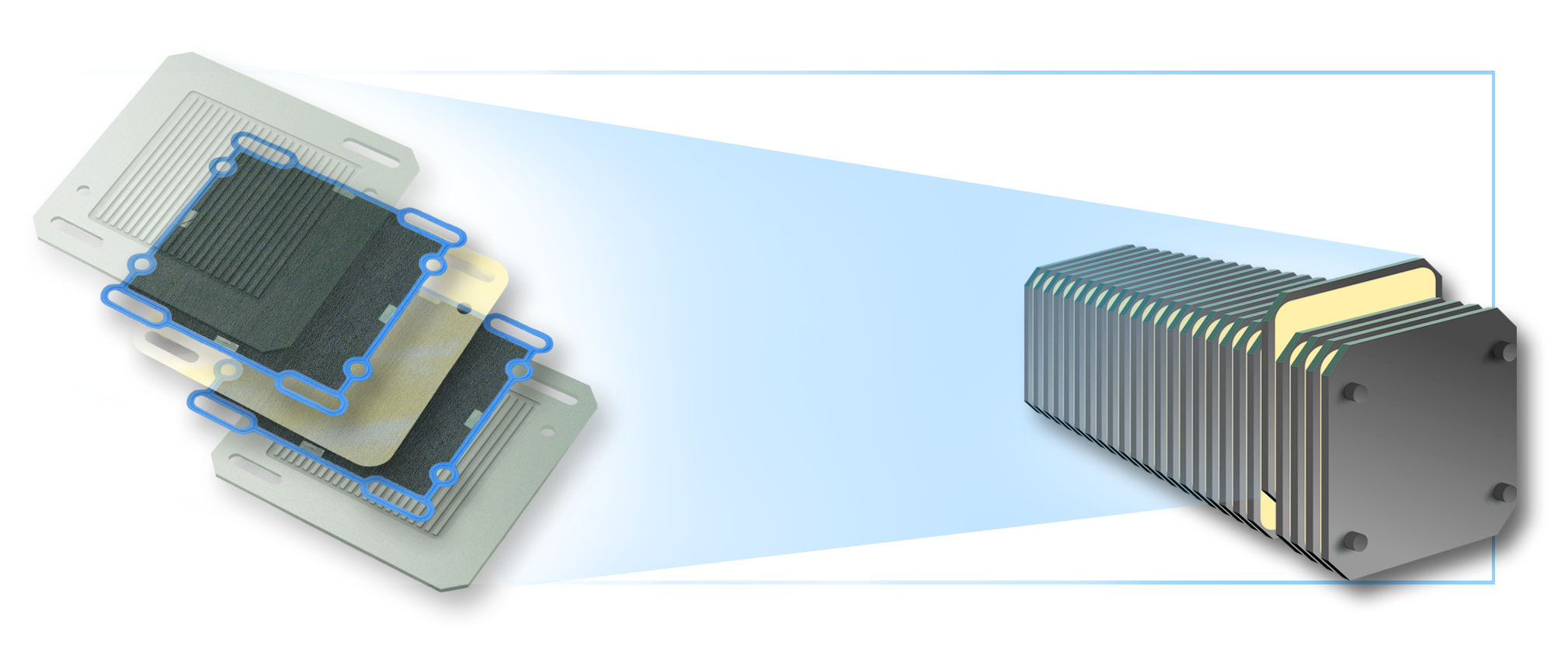

Freudenberg Fuel Cell Components Technology established

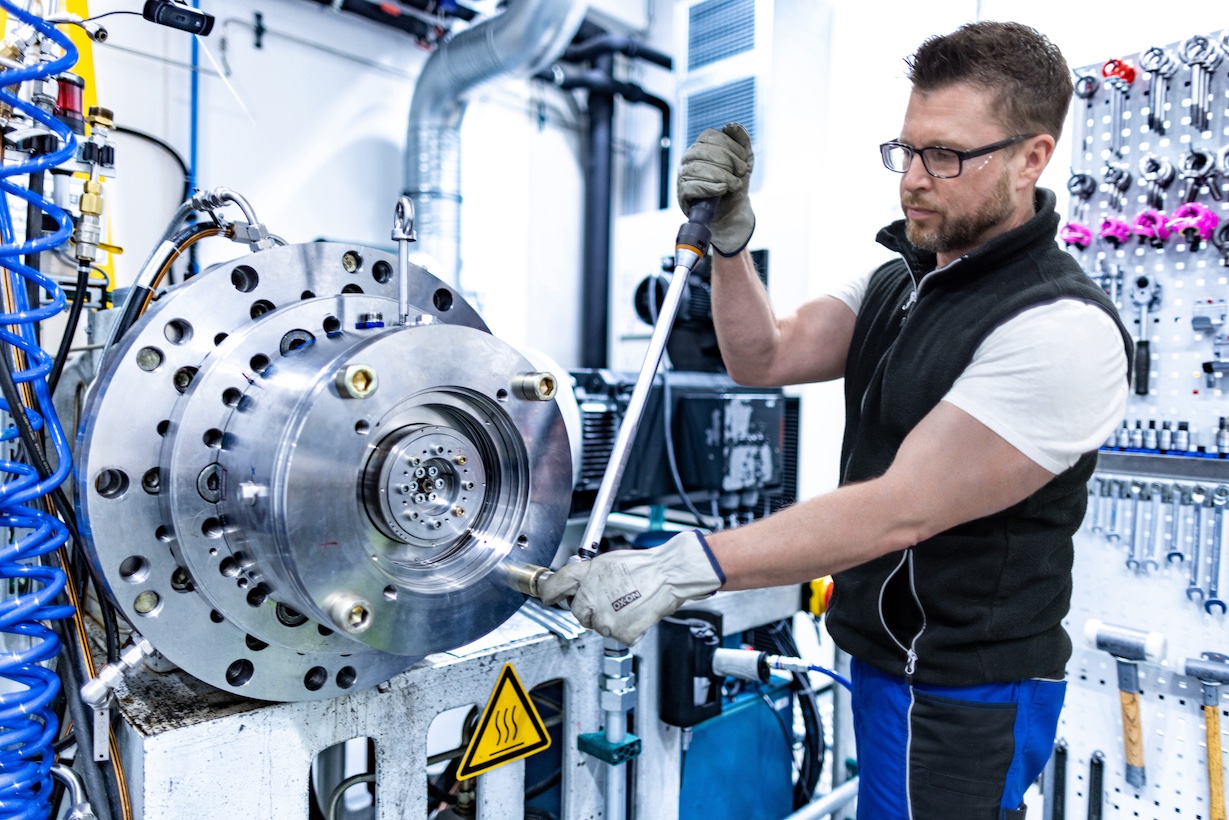

Freudenberg Fuel Cell Components Technology is established in 2001. This new business combines the competencies that have been built up in various Freudenberg activities since the 1990s. It develops components – including seals, gas diffusion layers, filters and humidifiers – for fuel cells, a promising energy technology.

At this time, the company employs around 30,000 people.

2002

Exit from leather production

Freudenberg bids farewell to its original leather business. Business relocations, reductions in production by large customers and a sharp rise in commodity prices have made the business unprofitable.

2004

Strategic acquisitions

With the acquisition of Burgmann Dichtungswerke based in Wolfratshausen near Munich, Germany, Freudenberg expands its sealing business to become a specialist in mechanical seals.

Freudenberg also buys US release agent specialists Chem-Trend to complement its chemical specialties activities.

The acquisition of the American company Jenline Industries, a manufacturer of silicone rubber products, brings Freudenberg into the medical technology industry.

2006

Expansion into new strategic business areas

Freudenberg strengthens its activities in the oil and gas industries, as well as in medical technology, through targeted acquisitions under the buy-and-build strategy. Among others, the company acquires Helix Medical, a manufacturer of high-quality precision moldings and tubing for medical, pharmaceutical and biotech applications.

2008 – today

2008

Sales slump due to crisis

The collapse of the financial markets in the USA leads to a massive recession in the real economy and spreads globally. Particularly hard hit are the company’s key automotive and mechanical engineering segments. In 2010, thanks to a wide range of measures, Freudenberg emerges strengthened from the crisis.

2009

LESS – emissions reduction through innovative sealing technology

With the launch of the Low Emission Sealing Solution Program (LESS), Freudenberg offers numerous innovative sealing solutions to reduce CO2 emissions in vehicles. They range from reduced-friction Simmerrings, innovative materials for transmission seals and weight-reduced housing elements, all the way to pressure-resistant sealing solutions for engine downsizing.

2010

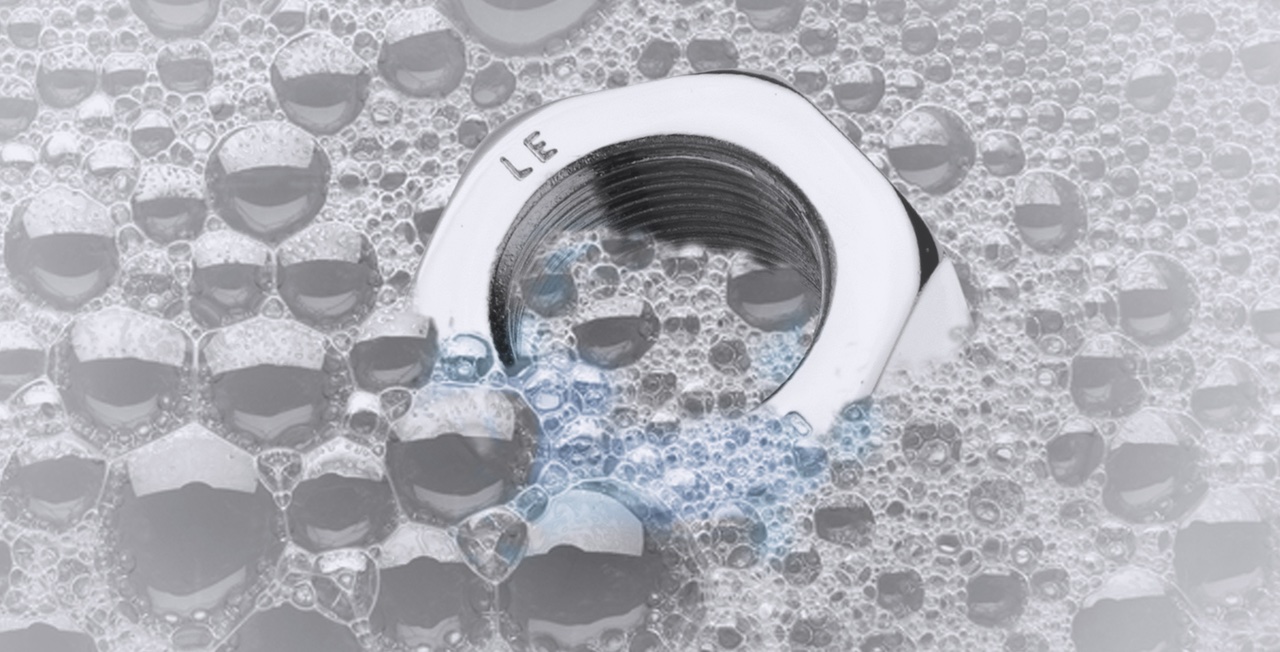

Development of a fourth pillar for chemical specialties

With the acquisition of SurTec in Zwingenberg, Germany, Freudenberg Chemical Specialities expands its portfolio to include a fourth pillar: surface finishing.

2012

Innovation: The Levitex® seal

The LESS program is extended. The new Levitex® crankshaft seal comes very close to the vision of a frictionless seal. This mechanical seal creates an air cushion and reduces CO2 emissions from vehicles by decreasing friction.

2014

Freudenberg joins UN Global Compact Initiative

In early 2014, the Freudenberg Group joins the Global Compact initiative launched by the United Nations, which commits signatories to adopt values-oriented and sustainable business practices.

The Freudenberg Group employs over 40,000 employees worldwide.

2018

Focus on new mobility technologies

Freudenberg starts expanding decades of know-how by developing technologically sophisticated components for fuel cells and batteries. Freudenberg strengthens its strategic position in alternative drive technologies by acquiring a stake in the Munich-based fuel cell manufacturer Elcore and the successive acquisition of the US battery manufacturer XALT Energy. Along with series production of key components, Freudenberg focuses on the development of complete electric drive systems for heavy-duty vehicles and ships with the founding of the Business Group Freudenberg e-Power Systems in 2022.

2020

The Covid-19 pandemic / Driving forward digital product solutions

The Covid-19 pandemic has an impact on the Freudenberg Group’s business development. There is a short-term drop in sales.

To keep employees healthy in the workplace, the company quickly makes mouth-and-nose masks available to them. Many of them come from the company's own production facilities in Japan, China, Germany and the United States.

Freudenberg begins pursuing digital solutions as the demand for a wide range of these products expands in all business fields. The smart seal sensors developed in 2020 for EagleBurgmann mechanical seals are an example of Freudenberg’s digital predictive maintenance solutions. The three-in-one sensors measure temperature, pressure, and vibration in mechanical seals and permit comprehensive monitoring.

2024

Reorganization of portions of the sealing business

Freudenberg forms a new Business Group: Freudenberg Flow Technologies. It consolidates the Business Groups EagleBurgmann and Freudenberg Oil & Gas Technologies, with the goal of optimizing sales synergies for long-term sealing solutions, in the oil and gas, energy, petrochemical, pharmaceutical, food and beverage, and water Segments.

The Freudenberg Group has more than 50,000 employees worldwide.

Discover Freudenberg

On the trail of the founder

His name, Carl Johann Freudenberg, is pivotal to today's technology company's success. Founded in Weinheim 175 years ago on February 9, 1849, by him and a partner, it swiftly rose to global prominence. The story of this enterprise is well-documented in modern archives. Yet, what does this record reveal about Carl Johann's personality and influence on Freudenberg's corporate values?

Read more

Why do we need company values?

Freudenberg’s founder formulated his Business Principles in 1887. They have been the foundation of the company’s culture ever since.

Read more